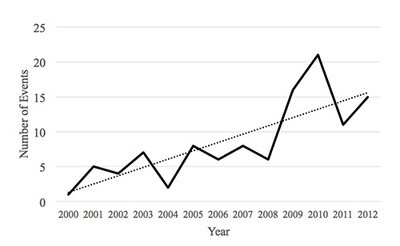

Active shooter incidents are incredibly frightening events that often have deadly consequences for individuals, and dire consequences for organizations. The term “active shooter” describes a “situation in which a shooting is in progress and an aspect of the crime may affect the protocols used in responding to and reacting at the scene of an incident” (Blair & Schweit, 2014, p. 4). Most government agencies in the U.S. define “active shooter” as an “individual actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a confined and populated area” (Blair & Schweit, 2014, p. 5). Since they have been studied, active shooter incidents have been steadily increasing over the years (Figure 1), causing increasing numbers of casualties, including many who have been killed or wounded (Blair, Martaindale, & Nichols, 2014; Blair & Schweit, 2014).

Figure 1: Active Shooter Events by Year

Image retrieved from https://leb.fbi.gov/2014/january/image/figure-1.-active-shooter-events-by-year.jpg/image_preview.

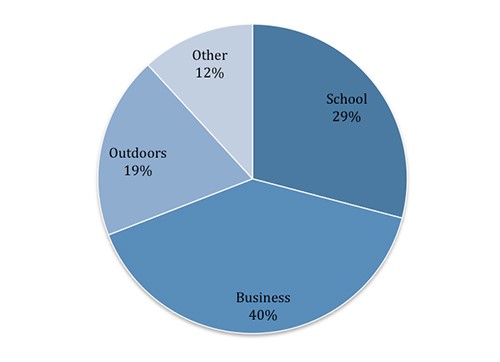

Unsurprisingly, most of these events have occurred at businesses (Figure 2). Because these data are cause for grave concern for any organization, private or public, it is no wonder that many organizations are coming to grips with the reality of considering ways of dealing with, managing, and preventing these kinds of incidents to occur.

Figure 2: Locations of Active Shooter Incidents

Image retrieved from (Blair et al., 2014).

Image retrieved from (Blair et al., 2014).

Obviously there are multitude of ways to approach this very important problem for security professionals. The first step is often raising awareness of this important issue, as many security professionals and organizations unfortunately remain in the dark about the frequency and/or severity of these types of events. Raising awareness alone is not enough; what is equally if not more important is to actively consider, implement, monitor, and refine a comprehensive security plan in order not only to deal with these incidents when they occur – as well as their aftermath – but also how to prevent them in the first place.

By now many security professionals have heard of the current rendition of the “best” response to an active shooter incident, involving the mantra “Run, Hide, Fight.” But let’s dive deeper into how this may actually occur in an active shooter situation. In reality, data on active shooter incidents have shown that 70% of such incidents ended in five minutes or less, with 37% ending in two minutes or less (Blair & Schweit, 2014). At the same time, the average (median) response time by law enforcement officers to the scene is about three minutes. These statistics indicate that civilians often have to make life and death decisions in a very short time, and in a very emotional situation. How to do so?

My many years of training athletes in Olympic judo competition gives us clues about how to approach the problem. These are also highly charged situations in which split second decisions need to be made when one is hyper aroused. In fact we have clocked athletes’ heart rates in competition upwards of 200 beats/minute. Given that that is what is occurring in real life, it becomes very clear very quickly that training in what to do in a very neutral, calm environment (e.g., a classroom lecture or workshop) has little or no bearing on making constructive changes to behaviors in the hyper charged situation. While classroom workshops on active shooter incidents are great for raising awareness, their potential in producing effective behaviors in a hyper charged situation is extremely limited. What is needed is training that simulates, as close as possible, the actual environment in which the desired behaviors need to take place. The most effective training will be that which produces that simulation well.

There are many ways to think about prevention as well. Research has increasingly documented the signs and signals of impending violence (Matsumoto, Frank, & Hwang, 2015; Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013, 2014; Matsumoto, Hwang, & Frank, 2013, 2014a, 2014b, 2016), much of which can be transformed into proactive detection capabilities to intervene before things escalate. Moreover, recent research on lone actors and other actors who perform violent acts against others has documented that many – upwards of 80 – 90% of these individuals – leak their plans and intentions in some way, shape, or form to others (Meloy & Gill, 2016; Meloy, Roshdi, Glaz-Ocik, & Hoffman, 2015). Heightened awareness of these signs and signals, and procedures for reporting these to security professionals may be of interest.

These are just some of the many ways to consider how to deal with, manage, and prevent active shooter incidents. Perhaps the most important factor to consider, however, and perhaps the most difficult, is to find the courage and conviction to truly deal with them in the first place.

References Cited

Blair, J. P., Martaindale, H., & Nichols, T. (2014). Active Shooter Events from 2000 to 2012. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, January. Retrieved from https://leb.fbi.gov/2014/january/active-shooter-events-from-2000-to-2012 website:

Blair, J. P., & Schweit, K. W. (2014). A study of active shooter incidents in the United States between 2000 and 2013. Washington, D.C.: Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation. U.S. Department of Justice.

Matsumoto, D., Frank, M. G., & Hwang, H. C. (2015). The role of intergroup emotions on political violence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 369-373. doi: 10.1177/0963721415595023.

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. C. (2013). The language of political aggression. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 32, 335-348. doi: 10.1177/0261927X12460666.

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. C. (2014). Facial signs of imminent aggression. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 1, 118-128. doi: 10.1037/tam0000007.

Matsumoto, D., Hwang, H. C., & Frank, M. G. (2013). Emotional language and political aggression. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 32, 452-468. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261927X12474654.

Matsumoto, D., Hwang, H. C., & Frank, M. G. (2014a). Emotions expressed by leaders in videos predict political aggression. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 6, 212-218. doi: 10.1080/19434472.2013.769116.

Matsumoto, D., Hwang, H. C., & Frank, M. G. (2014b). Emotions expressed in speeches by leaders of ideologically motivated groups predict aggression. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 6, 1-18. doi: 10.1080/19434472.2012.716449.

Matsumoto, D., Hwang, H. C., & Frank, M. G. (2016). The effects of incidental anger, contempt, and disgust on hostile language and implicit behaviors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12374.

Meloy, J. R., & Gill, P. (2016). The lone-actor terrorist and the TRAP-18. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 3, 37-52. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tam0000061.

Meloy, J. R., Roshdi, K., Glaz-Ocik, J., & Hoffman, J. (2015). Investigating the individual terrorist in Europe. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 2, 140-152. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tam0000036.