A longstanding debate about whether animals have emotions and feelings is being reshaped by new tools and concepts. Although animals can’t tell us how they feel, researchers like David Anderson, a biology professor at Caltech, believe that a connection exists between animal and human emotions.

In his book The Nature of the Beast: How Emotions Guide Us, Anderson describes research from his lab that suggests the brain circuits underlying human emotions have a lot in common with circuits found in mice and even fruit flies.

The Importance of Non-Human Emotions

Understanding whether non-human animals have emotions — and how they are formed if they do — could provide new insights into the mental health of humans, including understanding certain psychiatric disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Understanding whether non-human animals have emotions — and how they are formed if they do — could provide new insights into the mental health of humans, including understanding certain psychiatric disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

But emotion is tricky to study.

There isn’t a formal, widely held definition of what an emotion is, and neuroscientists, biologists, psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists and philosophers all have different views on its definition.

Although you can’t ask animals what they’re feeling, researchers who study animal “emotion” in reality actually study human analogs of emotion.

What is an Emotion?

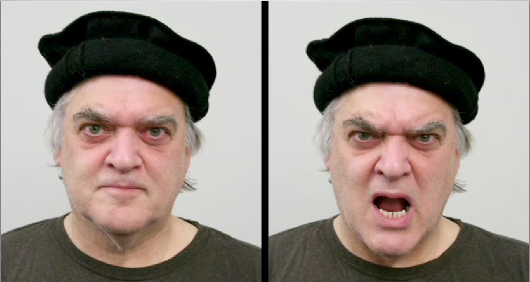

Dr. Matsumoto defines emotions as quick reactions to events that may impact our survival. They are unconscious, immediate, involuntary, automatic reactions to things that are important to us.

Most emotion scientists believe that emotions are triggered by how we evaluate events. These events include not only what happens around us, but also thoughts and feelings in our heads, because those thoughts and feelings can themselves trigger emotions.

This evaluation process is known as appraisal, and over the decades there have been tons of research that have led to many different appraisal theories of emotion. Although there are differences among them, these theories generally state that there are different emotions are triggered (or elicited) by different ways we appraise or evaluate events, and that different emotions are triggered by different appraisals.

Looking Past Emotions

Anderson says in order to study emotions in animals, scientists first need to set aside their own perceptions of what people typically think of as emotions, such as anger, fear, sadness or joy.

What lies beneath feelings, Anderson says, are brain states that produce certain behaviors. And that’s the part of emotion that scientists can study.

For example, Anderson’s lab has investigated fruit flies that become much more active when they see a moving shadow like the one cast by a flying predator.

In an article for NPR, Anderson states that sort of behavior is typical of a persistent brain state called defensive arousal. It’s present in both fruit flies and people, which is why Anderson believes studying fear in an insect or a mouse can reveal a lot about human emotions.

Anger and Aggression

Another human feeling that probably has its roots in animal emotion is anger.

Another human feeling that probably has its roots in animal emotion is anger.

There’s no way to know if animals have angry feelings, says Dayu Lin, a neuroscientist at New York University. But the sort of aggressive behavior associated with human anger can be found in fish, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Lin has studied the brain areas involved in aggression and one area of the brain appears to be critical. NPR states that in people, this region is near the bottom of the hypothalamus, just above the pituitary gland. And studies show that in mice and other animals, this clump of brain cells is part of a core aggression circuit.

In humans, anger is probably the most common emotion that we have that leads to feelings of regret later. Dr. Matsumoto doesn’t believe anger is inherently a “bad” emotion; getting angry can result in some good in our lives and in society. Anger, and all other basic emotions, exist for a reason.

In our evolutionary history, being angry (and disgusted and afraid and sad, etc.) was functional for us. That is, anger, as all other basic emotions, helped us deal with problems in our lives and in our environments in order to survive. In our evolutionary past, emotions like anger were important in order to deal with many life struggles. All our emotions allowed us to handle incredibly difficult events that required us to think with minimal conscious awareness.

Trauma, Fear and PTSD

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/requirements-for-ptsd-diagnosis-2797637_FINAL-5c12bdac46e0fb0001e7d6b3.png) Animal emotions are also helping scientists understand certain psychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Animal emotions are also helping scientists understand certain psychiatric disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

As stated in NPR, for a person with PTSD, even a minor event can produce a stress and fear response that lasts for hours, Ressler says. And there’s a parallel in animals.

A typical mouse will freeze when it hears a tone associated with a mild electric shock. But if the shocks stop coming, the animal soon learns to ignore the tone.

In both people and mice, trauma appears to alter a brain circuit involving the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. And in rodents, it’s possible to regulate that circuit.

“We now understand specific parts of the circuit that increase fear and other parts of the circuit that decrease fear,” or at least the animal version of that emotion, Ressler says.

The next step, he says, is to figure out how to tweak that circuit to reduce the fear response in people with PTSD.