Facial mimicry is known to be central to understanding the emotional states of others, but this exciting new study looks at the conditions under which we engage in such activity.

Emotional recognition is incredibly central to social interactions, and facial mimicry allows us to do so instantaneously. However, there is dispute over when we spontaneously or automatically engage in such behavior. It is this dispute which an exciting new paper in Plos One attempts to answer.

Specifically, the study authors are attempting to determine what factors make an individual engage in mimicry and what factors prevent them from doing so. This builds off of previous research finding that socio-ecological factors, like group membership and the identities of the people in question, inhibit or encourage the spontaneous mimicry necessary for emotional recognition.

While the role of such social factors is an ambitious one, the study authors sought a more manageable effort within that context. Previous research has indicated that facial mimicry occurs when there is an intention on behalf of the individual to deduce emotional states, and they sought to extend those findings in a more robust fashion, with an eye to the broader question.

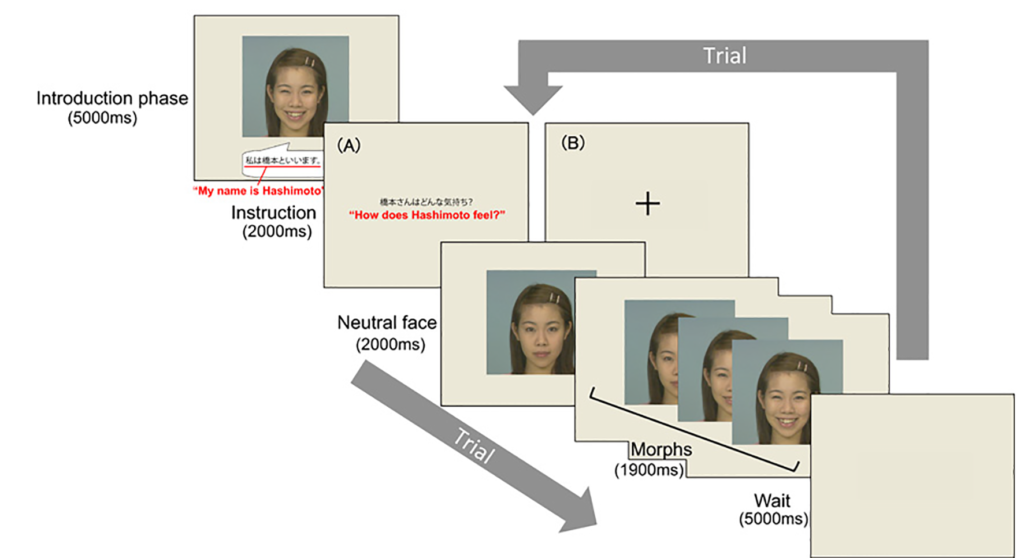

Participants were recruited from the Hokkaido University student body and asked to review a selection of photographs and videos of people’s faces exhibiting various emotions. During this process, their facial muscles were analyzed to detect the presence of facial mimicry, in a similar fashion as previous studies.

However, not all participants were asked to identify the emotions displayed in the various images. Instead, half of them were simply asked to record age, gender, and other demographic features. This required emotional recognition from only half of the group.

The hypothesis was that those primed to look for emotions would also spontaneously engage in facial mimicry, while those looking at demographic factors would not.

The electromyography (EMG) scans were able to detect facial muscle movement as a reasonable indicator of facial mimicry, and it turns out that those asked to detect emotions showed markedly higher rates of muscle movement than those who were not. This provides pretty compelling evidence in support of their hypothesis.

This is definitely one of those times where many readers may be unclear exactly why any of this matters. Since facial mimicry, and thus emotional recognition, are not automatic but tied to intention, the social context begins to be seen as more important.

Differing group membership, for instance, can actively inhibit the intention to recognize emotions, leading to ignorance or devaluing of emotions. This is particularly fascinating (and troubling) given our previous blogs on the role that group membership has on violence and anger.

What it also means is that you, as an aspiring people reader, can choose to engage in facial mimicry and choose to better read people. This is something we can learn how to do, which is what Humintell tries to do, but it is also something we have to want to do.